According to Jean Kilbourne, “Mass communication has made possible a kind of national peer pressure that erodes private and individual values and standards,” manifested in the media texts dominating American culture, and adversely affecting social groups (Kilbourne). This pressure for social acceptance is embedded in advertisements, particularly those selling an illusion more than a product. A semiotic analysis of Sean Combs’s perfume ad, juxtaposed against Aviance’s Night Musk cologne advertisement epitomizes the degeneration of social equality between sexes. Despite gender differences in their target audiences and dissimilar historical contexts, both Sean John’s Unforgivable Woman and Aviance Night Musk fragrance ads exemplify male dominance and the objectification of women in their strategic marketing appeals to the consumers.

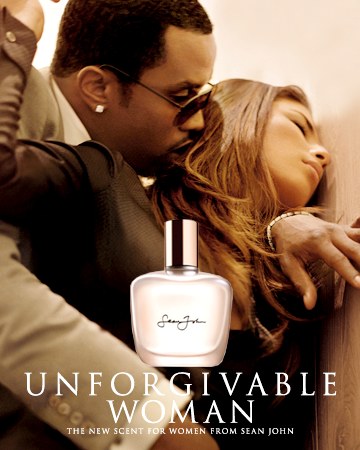

As a modern brand advertising in the 2000s, Sean John’s perfume ad for Unforgivable Woman is directed at young women, utilizing consumer association with lovemarks and affective economics techniques. Sean Combs, more popularly known as Puff Daddy or P. Diddy, founded his company Sean John in 1998, hopes of creating a multi-product enterprise including music, clothing and television shows (Pegler). As a result, his brand is not only associated with his own celebrity persona, but has become a lovemark, a brand that “reach[es] your heart as well as your mind, creating an intimate, emotional connection that you just can’t live without” (Lovemarks). Sean John’s logo, a distinctive cursive signature, is present on all Combs’s products including sportswear, fashion apparel for men and later women, accessories and of course fragrances, so that his dedicated fans can recognize the new products he has released. P. Diddy, a rap artist who became entrepreneur mogul Sean Combs, uses his own fame and recognition to advertise his products. Fans of his music are likely to buy records that he has produced, clothes he has made, and perfume he sells, due to their “loyalty beyond reason” characteristic of a lovemark brand (Lecture, 15 July 2010). Typically, Combs’s dominating presence in his perfume ad for Unforgivable Woman released in 2006 is selling not so much the product, but rather himself. The target audience of the advertisement, which is likely to be featured in a women’s magazine like Glamour or Cosmopolitan, is the demographic group of women in their teens to late twenties who read these magazines, a large part of the “niche market that has gained considerable attention…a major market for films, TV Shows, CDs…and fashion” (Grossberg et al 109). This demographic segment, in addition to the target audience for women’s magazines and the advertisement itself, is the generation that remembers Sean Combs as Puff Daddy, then consuming his music and now his products. The women of the target audience who associate themselves with Sean John consider it a lovemark, and thus are more likely to buy the fragrance. The ad itself features Sean Combs with his arms around a woman who has her eyes closed, a romantic intimacy that is an example of affective economics, a “marketing strategy that tries to determine the emotional underpinnings of consumer buying decisions” (Lecture, 15 July 2010). A woman’s yearning for the close embrace of a man makes this ad relatable to young females, and therefore more profitable. The historical context of this ad is the modern era, targeted towards young women through the use of affective economics and lovemarks. The marketing strategies of affective economics and lovemarks are representative of advertising techniques of the new age, fitting for this 2006 ad.

Aviance’s Night Musk, on the other hand, is a 1983 advertisement aimed towards working males in their twenties and thirties, also using affective economics as a marketing tactic. The Night Musk ad depicts a young man coming home after work, an advertisement likely to be found in a men’s magazine that is likewise geared towards consumers of the young male professional demographic group. The slogan, “Put it on…and have an Aviance night” is catered toward men represented in the Aviance advertisement, who under the illusion of the ad, would buy the cologne in hopes of sexually conquering an attractive woman. In this way, Aviance uses affective economics to appeal to the sexual desires of aroused men by selling the experience of a pleasurable night more so than the Nigh Musk fragrance. This type of “pseudo-spiritual marketing” eliminates consumer regard for the actual product, but rather allows the advertisements of Aviance to “become more than just a mark of quality [and] become an invitation to a longed-for lifestyle” (The Persuaders). The Night Musk ad was released about thirty years ago, during the transition between the early advertising of product qualities of the 1950s and the new age of emotional branding and celebrity endorsement (The Persuaders). Although the target audience of Aviance’s Night Musk is primarily young males, the consumers have been categorized into this specific demographic, similar to the audience segmentation of Sean John’s Unforgivable Woman.

The Unforgivable Woman by Sean John ad contains several indicators of male dominance and female objectification. The product name itself is evidence of the woman’s burden, as “Unforgivable Woman” alludes to one woman in particular: Eve, tempted to eat the forbidden fruit of the Garden of Eden, an “unforgivable” mistake after which women have been considered inferior, evident in modern advertisements. Although this product is targeted toward female consumers, a man—who is the creator of the product—is a large focus of the advertisement, signifying the masculine presence in not only the product Sean Combs endorses, but also in the consumer choices a female customer makes. A woman may buy this product, but it was sold to her by a famous and influential man who is immersed within the product—his face in the advertisement, his signature on the bottle, and his fame’s influence over the consumer’s purchase. The syntagmatic organization of the text refers to, “its organization, how its signs are connected in time or space” that is vital to the overall meaning of the advertisement (Grossberg et al). For example, Sean Combs’s overshadowing position in the advertisement is domineering, pinning the woman against a wall and territorially wrapping his arms around her waist and neck, not protectively but rather overbearingly, indicating his authority over her. While the woman’s head is passively tilted and dependent on the wall and his arm behind her for support, the man’s head is steady and independent, in control of both of them. Sean Combs’s accessories are a sign, or “elementary unit of a system of meaning,” of wealth and superiority (Grossberg et al). He has an expensive-looking watch, a diamond earring, a large ring and sunglasses, whereas the woman is unadorned, therefore perceived as simple and lesser. The syntagmatic dimensions of this media text are indicative of the masculine superiority evident in the advertisement. Moreover, the paradigmatic organization, “the potential substitutions that one can make without changing the syntagmatic relationship” further reveals the male-dominated elements of the advertisement (Grossberg et al). For instance, in the ad Sean Combs’s eyes are open and alert, instead of closed where he would be considered emotional and therefore vulnerable. His detached countenance is also proof of his sense of superiority—if he were attentive and truly intimate with the woman, she would have some dynamic of power over him as well. The absence of physical indicators of the man’s romantic engagement creates a hierarchy in which the male is on top. Therefore, Sean Combs’s Unforgivable Woman ad indicates evidence of male superiority in advertising culture.

Aviance’s ad similarly contains substantiation of male supremacy in its campaign to sell cologne as an illusion of sexual conquest. The most overt example is the woman’s revealing leg framing the ad. She is wearing a bright red high heel, indicative of passion and sexuality. The woman is lying down on the bed, suggesting that she has been at home, idly waiting for her lover to come home from work. Housewives and women who do not work are perceived as helpless and dependent on their male counterparts who provide for both of them, eliminating any element of gender equality from this ad. Furthermore, the face of the woman is not even included and she is regarded as irrelevant except for her seductive bare leg, whereas the man is completely visible. The syntagmatic organization of the ad shows the man as the centerpiece, the main attraction, with rays of sunshine cast upon him like a spotlight. The woman’s legs surround him, glorifying his masculinity to communicate to consumers that the Night Musk cologne will attract a similar and desirable lifestyle. Both the woman and the man have their legs split, a sexual invitation drawing attention to the sexuality promised by the Night Musk product. Paradigmatically speaking, the inclusion of the woman’s face and body would give her dignity and respect, but instead the ad uses an anonymous display of temptation, objectifying women as sexual pleasure and not equal beings. Dressing the man in pajamas or house clothes instead of a suit and tie would suggest that he too is a homebody, and not a working man of self-worth and respectability, but the ad wishes to express the higher value of a man versus a woman.

Despite the different target audiences of these ads and their distinctive cultural periods within which the brands marketed their products, both advertisements objectify women while exalting the man in their campaign to sell fragrances. Jean Kilbourne argues that advertisers transmit messages emphasizing the need for superficiality, beauty and flawlessness, and “women are especially vulnerable because [their] bodies have been objectified and commodified for so long” (Kilbourne). By comparing fragrance ads released over a span of thirty years, the sexism in advertising proves to be as prevalent and socially destructive today as it was in 1983.

Works Cited

Aviance Night Musk for Men. Digital image. PZR Services. Web. 19 July 2010.

Grossberg, Lawrence, Ellen Wartella, and D. Charles Whitney. MediaMaking: Mass Media in a Popular Culture. London: Sage, 1998. Print.

Kilbourne, Jean, (from Gender, Race and Class in Media), “The More You Subtract, The More You Add: Cutting Girls Down to Size”

"Lovemarks: Sean John (Nomination)." Lovemarks: the Future beyond Brands. Saatchi & Saatchi, 2010. Web. 19 July 2010.

Media Studies N10. Lecture, 15 July 2010

Pegler, Martin M. "Designer Boutiques." Stores of the Year: No. 15. New York: Visual Reference, 2005. 82. Print.

The Persuaders. Dir. Barak Goodman and Rachel Dretzin. PBS. Frontline, 09 Nov. 2003. Web. 20 July 2010.

Sean John Unforgivable Woman. Digital image. Ace Show Biz. Web. 19 July 2010.